Ojiya, Niigata Prefecture –

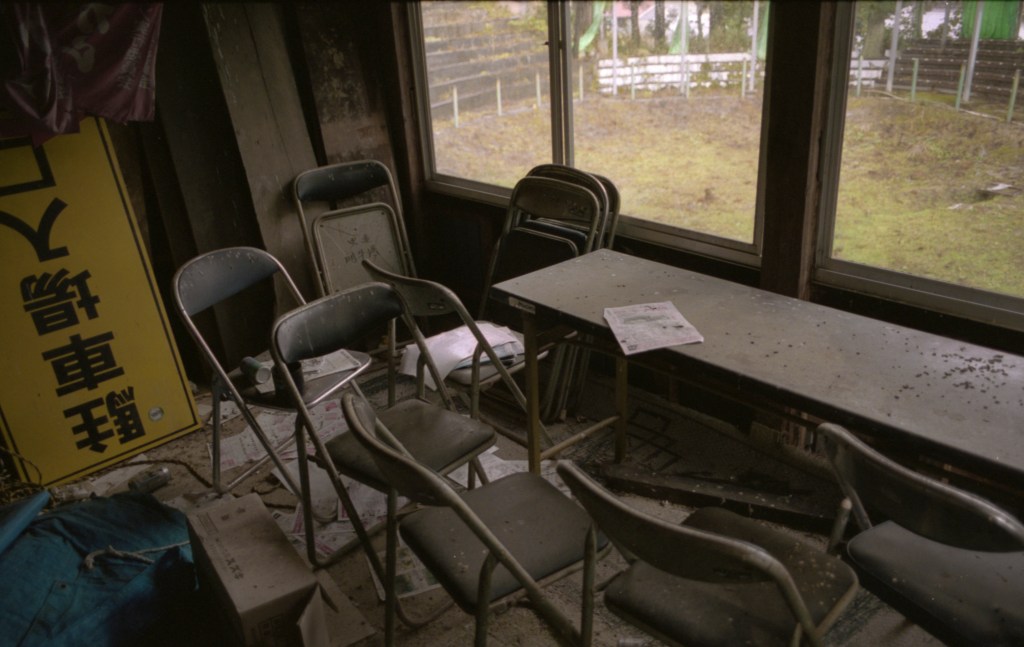

Live, the arena where tsunotsuki matches are held once a month is smaller than I expected. It starts to rain, and the silence that pervades the woods around us gives way to the liquid murmur of drops bouncing on the leaves.

Ojiya is located just over twenty kilometers from the Sea of Japan, on the country’s west coast. It is surrounded by mountains and experiences heavy snowfall in the winter. It is a mountainous village through and through. This place enjoys some international fame for being one of the most productive centers for breeding Japanese carp in the country, as well as for preserving the exclusive production of textiles known as Ojiya chigimi.There is a tradition in Ojiya, shared by only a few other cities in the archipelago, that has ingrained itself in the identity of the region so deeply that it has generated the town’s mascot. When it comes to mascots, known as yura-chara, the Japanese are serious and understand that promoting local tourism with the right mascot can bring national fame to the area in a short time, in the form of keychains and TV appearances. Ojiya’s yura-chara is a bull named Yoshita-kun, evoking the traditional bullfighting. Referred to in this part of the country as tsunotsuki, and in other areas as ushi-zumo or togyū, bullfighting is an ancient tradition strongly tied to Shinto philosophy. The priest responsible for blessing the game field and the breeders at the start of each competition season, following an ancient ritual, tells us about its origins. In Japan’s past, bulls were used for work in the rice fields. They were valuable members of every farming family, cared for just like expensive car. At the core of Shinto practice were numerous rituals aimed at securing a good harvest – a belief was widespread that religion emerged from rice cultivation and the need to offer prayers to the gods for a bountiful harvest. One of these rituals evolved into a performance that showcased the strength of two animals to entertain the gods.

It was immediately established that there could be no winners or losers, otherwise, the family of the defeated bull might face a season of hardship. Furthermore, the bulls were not to suffer either minor or lethal injuries, both to ensure the safety of the valuable work companion and to avoid offending the gods, who were sensitive to the sight of blood. Lastly, since the events were of a religious nature, gambling was prohibited. This is how a tradition developed that places the relationship between humans and animals at the forefront.The bulls, usually of the Nambu breed from Iwate Prefecture, resemble mythical creatures, imposing and peaceful. Typically, a family owns only one animal, which is cared for as a member of the family. In households with a bull, there are more photos of the animal hanging than of the children. Throughout the town, in bars, restaurants, or municipal offices, there are posters, photographs, announcements, or caricatures related to tsunotsuki.

The practice has much in common with traditional sumo and is said to share its Shinto origins. Similar to sumo, in tsunotsuki, the combat area is blessed with salt and participants drink sake before entering the ring to purify themselves. Many other similarities exist between the “human” version of sumo and tsunotsuki. The former has been plagued by scandals for years that have compromised its nobility, causing the sport to struggle to keep pace with modernity and regain its former glory.

Tsunotski, on the other hand, has remained a simple and festive celebration, free from any negative shadows, and recently seems to have preceded traditional sumo by accepting women in the ring. In sumo, even today, it is forbidden for women to step onto the sacred combat ground. Until recently, the same was true for the “animal” version of this sport. However, in 2018, the first female breeder was admitted to the Nagaoka tournament.Like sumo wrestlers, bulls are also divided into categories, and the coveted title is yokozuna

This ancient tradition brings the town’s residents together in the warmer months for a mountain festival in the east, in Higashiyama. From May to November, families that raise a bull for the matches know that the festival day is the pinnacle of the life they share with the animal. Their days are marked by its needs, as it requires quality food, rest, and training to prepare for the competition. Venturing into the countryside outside the city, it’s not uncommon to see these enormous animals on a leash. Like oversized gentle giants, the bulls walk slowly, led by a rope attached to the ring in their nose. Owners skillfully maneuver these ton-sized animals, making them walk uphill to strengthen their leg muscles, and stopping near large trees, allowing them to rub their horns and practice headbutting.

During the matches, a key role is played by the seko, whose task is to choose the best moment to separate the bulls. Generally, since the match must always end in a tie, the seko signals when both bulls are still pushing with equal force. To separate the animals, ropes are used to immobilize one hind leg, while attempts are made to grip the animal’s nose to thread another rope through the nose ring. The seko is the star of the match, and the skill and composure with which they handle the heavy animal earn them applause and cries of admiration.

Typical of the Japanese is their almost manic attention to detail. It’s no surprise that more than twenty-one techniques have been delineated for the bulls to use in winning a match (in sumo, there are eighty-two techniques). At the entrance of the arena is a large stone (mimamori iwa) whose profile resembles that of a bull. An enormous omozuna, made to celebrate providence, adorns the stone. It is said that an earthquake broke the stone and gave it the shape it has today. The omozuna is a manifestation of the spirit of the bulls that have fought in the location where it stands. It is a decoration composed of three intertwined cords that is placed on the bulls to ensure victory in a tournament. According to tradition, the more people participate in the creation of the omozuna, the more strength and energy the bull will accumulate before the match.

What makes this tradition special is its ability to bring to the surface some of the fundamental aspects of the philosophies that permeate the spiritual forms of Japanese culture, such as the relationship between humans and animals, and thus with the natural world, which is also one of the cornerstones on which Japanese thought is based. In this celebration, which goes beyond the periodic collective event and requires unwavering dedication from the breeders, one can observe the layering of meanings that envelop the core of Japanese culture.

(english translation by chatgpt)

IN LOTTA PER GLI DEI (versione originale )

Dal vivo, l’arena dove una volta al mese si tengono gli incontri di tsunotsuki è più piccola di come mi aspettavo. Inizia a piovere, il silenzio che pervade i boschi attorno lascia spazio al brusio liquido delle gocce che rimbalzano sulle foglie. Ojiya si trova a poco più di venti chilometri dal Mar del Giappone, sulla costa ovest del paese. È circondata dalle montagne e d’inverno nevica copiosamente. Essa è in tutto e per tutto un paese di montagna. Questo posto gode di una certa fama internazionale per essere uno dei centri di allevamento di carpe giapponesi più rinomati del paese, oltre a conservare l’esclusiva produzione di tessuti chiamati Ojiya chigimi.

C’è una tradizione a Ojiya, condivisa da poche altre città dell’arcipelago, che è penetrata nell’identità del territorio in maniera così profonda da aver generato la mascotte del paese. Quando si tratta di mascotte, le cosiddette yura-chara, i giapponesi non scherzano, e sanno che promuovere il turismo locale con la mascotte giusta può conferire al territorio una fama nazionale nel giro di poco tempo, sotto forma di portachiavi e apparizioni in TV. Lo yura-chara di Ojiya è un toro, Yoshita-kun, e rievoca la tradizionale lotta tra tori. Definita in questa parte del paese con il nome di tsunotsuki, in altre zone ushi-zumo o togyū, la lotta dei tori è una tradizione antica fortemente legata alla filosofia scintoista. A raccontarci le sue origini è il sacerdote scintoista incaricato di benedire, a ogni inaugurazione della stagione di gara, il campo di gioco e gli allevatori, secondo un rituale antico. In passato, in Giappone, i tori venivano destinati al lavoro nelle risaie. Erano membri preziosi di ogni famiglia contadina, che si prendeva cura di loro proprio come si farebbe con una auto costosa. Alla base della pratica scintoista vi erano numerosi rituali per propiziarsi un buon raccolto – è diffusa, infatti, la credenza secondo cui la religione sia nata proprio dal coltura del riso e dalla necessità di offrire voti agli dei per ottenere un buon raccolto –, uno di questi rituali divenne quello di offrire intrattenimento agli dei con uno spettacolo che metteva a confronto la forza di due animali. Da subito si stabilì che non ci potessero essere vinti o vincitori, altrimenti la famiglia del toro sconfitto sarebbe potuta andare incontro a una stagione di miseria. Inoltre, i tori non dovevano subire ferite leggere né letali, sia per garantire ai partecipanti l’incolumità del prezioso compagno di lavoro sia per non offendere gli dei, sensibili alla vista del sangue. In ultimo, essendo gli incontri di natura religiosa, le scommesse erano bandite. Cosi si è sviluppata una tradizione che pone al primo posto la relazione tra l’uomo e l’animale.

I tori, in genere di razza nambu, originari della prefettura di Iwate, sembrano bestie mitologiche, imponenti e pacifiche. Solitamente una famiglia possiede un solo animale, che cura come un membro della stessa. Nelle case di chi possiede un toro, sono più le foto appese dell’animale che quelle dei figli. In tutta la città, nei bar, nei ristoranti o negli uffici comunali, ci sono poster, fotografie, annunci o caricature legate allo tsunotsuki. La pratica ha molto in comune con il sumo tradizionale e si dice ne condivida anche le origini legate al credo scintoista. Come nel sumo, anche nello tsunotsuki il terreno del combattimento viene benedetto con il sale e i partecipanti bevono sake prima di entrare in campo per purificarsi. Molte altre sono le similitudini con la versione “umana” del sumo. Quest’ultimo è ormai da anni oggetto di scandali che ne hanno compromesso la nobiltà, tanto che tale sport fatica a mettersi al passo con la modernità e a ritrovare lo splendore di una volta. Lo tsunotski, invece, è rimasto una celebrazione semplice e festosa, priva di qualsiasi ombra negativa, e ultimamente sembra aver anticipato il sumo tradizionale accettando le donne sul ring. Nel sumo, ancora oggi, viene proibito alla donna di calpestare il sacro terreno di combattimento. Fino a poco tempo fa, era lo stesso per la versione “animale” di questo sport, ma nel 2018 la prima donna allevatrice è stata ammessa al torneo di Nagaoka. Come i lottatori di sumo, anche i tori sono suddivisi in categorie, e il titolo di yokozuna è il più ambito. Questa antica tradizione riunisce gli abitanti della città nei mesi più caldi in una festa tra le montagne a est, a Higashiyama. Da maggio a novembre, le famiglie che allevano un toro per gli incontri sanno che il giorno di festa è il momento culminante della vita che si condivide con esso. Le giornate infatti sono scandite dalle sue necessità, poiché per affrontare i giorni di gara ha bisogno di cibo di qualità, riposo, ma anche allenamento. Se ci si aggira nelle campagne fuori dal centro urbano, non è raro vedere questi enormi animali al guinzaglio. Come grandi cagnoloni fuori misura, i tori camminano lentamente, condotti grazie a una corda legata all’anello al naso che li caratterizza. I proprietari manovrano con maestria un animale di qualche tonnellata, lo portano a camminare in salita per rafforzare i muscoli delle zampe e si fermano in prossimità di grossi alberi, permettendogli di strofinare le corna e di allenarsi a dare testate. Durante gli incontri, un ruolo chiave lo riveste il seko, il cui compito è quello di scegliere il momento migliore per separare i tori. Generalmente, dovendo l’incontro finire sempre in parità, il seko dà il segnale quando entrambi i tori stanno ancora spingendosi con forza pari. Per separare gli animali vengono usate delle corde che ne bloccano una zampa posteriore, mentre si tenta di afferrare il naso dell’animale per far passare un’altra corda all’interno dell’anello al naso. Il seko è la star del match, e la maestria e la freddezza con cui gestisce il pesante animale gli assicurano applausi e grida di ammirazione. Tipica dei giapponesi è l’attenzione quasi maniacale ai dettagli. Non stupisce che siano state delineate più di ventuno tecniche messe in pratica dai tori per vincere un match (nel sumo le tecniche sono ottantadue).

Alle porte dell’arena, si trova un grande masso (mimamori iwa) il cui profilo ricorda proprio quello di un toro. A ornamento della pietra è stato messo un enorme omozuna, realizzato per celebrare la provvidenza. Si racconta che fu un terremoto a rompere la pietra e a farle assumere la forma che ha oggi. L’omozuna è una manifestazione dello spirito dei tori che hanno combattuto nel luogo in cui si trova. Si tratta di una decorazione composta da tre corde intrecciate che viene fatta indossare ai tori per propiziare la vittoria di un torneo. Secondo la tradizione quante più persone partecipano alla realizzazione dell’omozuna tanto più il toro accumulerà forza ed energia prima del match. Ciò che questa tradizione ha di speciale è la capacità di far affiorare alcuni degli aspetti fondamentali delle filosofie che permeano le forme di spiritualità della cultura giapponese, per esempio il rapporto tra uomo e animale, e quindi con il mondo naturale, che è anche uno dei cardini su cui si fonda il pensiero nipponico. In questa celebrazione, che va oltre la periodica manifestazione collettiva e che comporta una dedizione da parte degli allevatori senza soluzione di continuità, si può osservare, dunque, la stratificazione di significati che avvolgono il nocciolo della cultura giapponese.